Christopher Pastore is the Associate Director of Humanities and Social Sciences Programs at LPS and a Lecturer in the History of Art department. He is the Director of the Master of Liberal Arts program and leads seminars in Visual Studies in topics ranging from Digital Art History to Gardens and Landscape Architecture. He served as the inaugural Barnes Foundation Program Director for Understanding World Art where he taught courses on Renoir and El Greco. He received his Ph.D. in the History of Art from Penn with a dissertation that explored villa ideology in the early modern Veneto. His publications include studies of allegories and gender identity, garden aesthetics and Renaissance theory, and the influence of the Islamic world on Venetian gardens. He is slowly revising a manuscript on Sixteenth Century Italian villa culture tentatively titled Cultivating Antiquity.

Albrecht Durer, The Syphilitic, 1496, and

Syphilis: The Virgin Mary and Christ child bless the afflicted. Woodcut series, 1496.

Giorgio Vasari, Benvenuto Cellini, and Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the head of Medusa, 1545–1554.

Agnolo Bronzino, An Allegory of Venus and Cupid, 1545. Full view and detail of Jealousy or a Syphilitic Woman.

Detail of Bronzino’s Jealousy and Enea Vico Dolor or Sorrow, c. 1560.

Luca Giordano, Youth Tempted by the Vices, 1664.

Jan van der Straet or Jacopo Stradano, Allegory of America, 1587–1589,

and Orazio Farinati, Allegory of America, 1595.

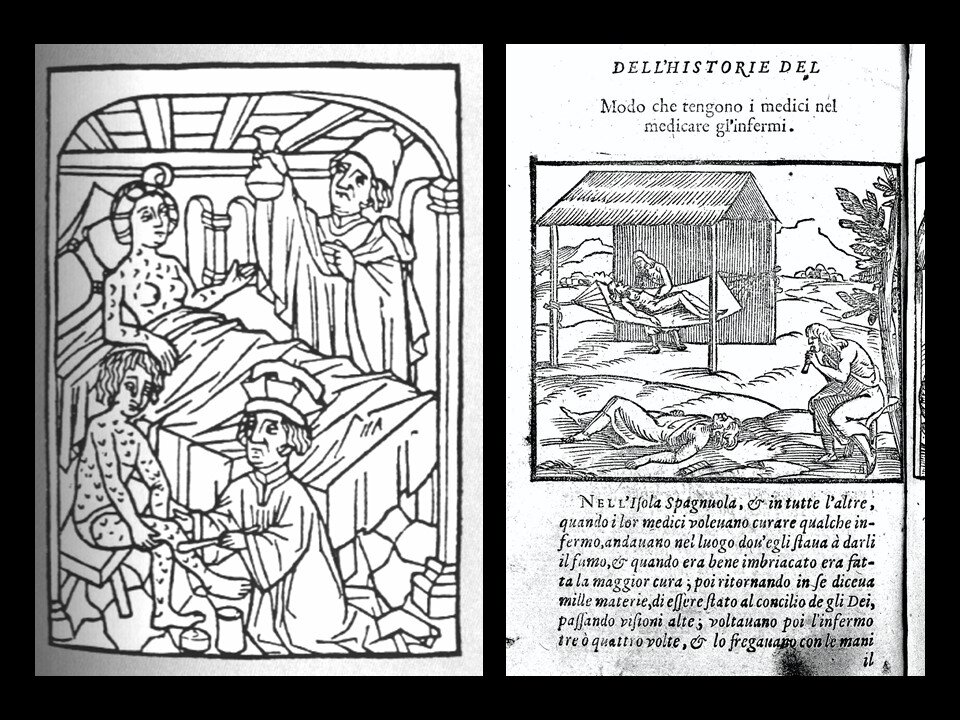

Woodcut, Syphillis treatment, Vienna, 1498 and “the methods of American Doctors” from Girolamo Benzoni, La Historia del Mondo Nuovo, Venice, 1565, p.55.

Jan Van der Straet, Guaiacum and Venereal Medicine, 1580, Plate 6 of Philips Galle’s Nova Reperta, Antwerp c. 1600

Hieronymus Fracastorius (Girolamo Fracastoro) shows the shepherd Syphilus and the hunter Ilceus a statue of Venus to warn them against the danger of infection with syphilis. Engraving by Jan Sadeler I, 1588/1595, after Christoph Schwartz.

Gonzalo Fernandez di Oviedo, Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierra firme del mar océano. Séville. First part. Maize, 1535. Map of the city of Mexico in G.B. Ramusio's Delle Navigationi et Viaggi, volume 3.

Guaiacum officianale.

essay

Fracastoro and the Holy Wood

Christopher Pastore, University of Pennsylvania

In the second half of 2021 we are faced with an ongoing pandemic that has impacted work and life, commerce and education, social life and individual behaviors. We are variously navigating a third or fourth wave of Covid-19, surging case counts as a result of the Delta variant, battles over masking and vaccinations, and exhaustion after 18 months of working in basements on remote desktop and meeting friends and family on Zoom or Facetime. One thing that has emerged as a through-line over the past two years is the push and pull over the inherent benefits and potential pitfalls of globalization. The struggle to identify and defeat the disease has been a global scientific effort, but many members of society have retreated behind fear and xenophobia while local antagonism imperils our ability to follow the science and enable our common humanity to get back to the business of surviving all the other challenges we face today.

I wrote this essay some years back, with no expectation that what I learned about early modern science and sexually transmitted diseases would have any relevance beyond the boundaries of my study of the Sixteenth-Century Veneto and the character of the elite members of Venetian society who invested in and developed land across the provincial terraferma. However, the rapid and welcome sequencing of the Covid-19 virus and the development of multiple vaccines, several of which break entirely new ground in the use of mRNA as the delivery vehicle, suggested to me that readers might be interested in the way Girolamo Fracastoro and his colleagues recognized that diseases were a global phenomenon that traveled alongside goods and individuals on the ships slowly covering more and more of the planet in the 1500s. Moreover, understanding how diseases infected individuals and how they moved from population to population proved fascinating to Fracastoro and his audience, especially when sickness—and potential cures—overlapped with the investigation of new discoveries across the oceans of indigenous peoples, new plants, and alternative therapies and medicines that other cultures used to fight off or treat diseases that were sweeping across Europe. Although there is no comparison between the scope of syphilis and the impact of Covid-19, and Fracastoro’s research interest in Guaiacum as a new drug of choice for this horrible affliction and the powerful and efficacious vaccines now being used to beat back Covid-19, please consider what follows as a riff on the inherent problems scientists face as they struggle to understand the world, when business and politics may not be similarly willing to accept that we are all in this together as a global community.

Fracastoro and the Holy Wood

Syphilis, the disfiguring venereal disease also known as the “French sickness,” the “Spanish sickness,” and the “Neapolitan disease,” was a dramatic and new scourge that swept across Europe in the last decade of the fifteenth century and left a vast number of dead and horribly mutilated survivors in its wake. A bacterial infection caused by the introduction of the spirochete Treponema pallidum through mucous membranes or other skin lesions, syphilis was a remarkably painful disease that exploded on the scene and demanded the attention of governments, institutions, and physicians as syphilitics became incapacitated and the disease threatened to mutate into a pandemic. The previously unknown ailment afflicted young and old, male and female, and its connection with both sexual intercourse and new theories of transmission inspired authors and artists to characterize the disease as a plague on the lustful and a symbol of the dangers implicit in the European thirst for conquest.

Benvenuto Cellini’s celebrated contraction of syphilis may be one of the best-known cases of the disease in early modern Italy. His account of his suffering and treatment could be thought of as a clear reminder of the increasingly global reach of disease, while it also helps us better understand the increasingly international scope of the arts and culture in the Renaissance. Cellini, who contracted the disease around 1533 or 1534, argued that a “French serving girl” infected him; he began to develop symptoms such as red, penny-sized blisters approximately four months after he “had” her, as he recalled. In his autobiography he noted that his physicians resisted the term “French sickness” for the “pox” despite the clear correlation between his contraction of the disease and the contemporary connection of these symptoms to sex and the relatively recent appearance of syphilis in Europe during the Italian wars and the French occupation. The “best doctors” in Rome failed to relieve his suffering; so, against their advice he began a treatment plan that featured the medicinal use of lignum vitae in liquid suspension. The “holy wood” improved his health and permitted him to return to normal physical activity. A dramatic relapse with high fever followed a hunting expedition in a swamp, but his access to and willing use of the new American medicine brought him back to the pink of health even as his Roman physicians lectured him on the potential ill affects of this treatment for his pox. This paper will discuss several aspects of the treatment of this new disease and the role played by two men, the Veronese polymath Girolamo Fracastoro and the Spanish governor of Hispaniola Fernando Gonzalo de Oviedo, in the introduction of a new treatment, based on a New World tree, Guaiacum Officinale or “Lignum Sancta,” to Europe.

Two paintings by Bronzino and Luca Giordano remind us of the horrific experiences of those who contracted the disease and allow us to think about the contemporary recognition of the syphilitic as a hostage to the pursuit of physical pleasure and the divine punishment such uncontrollable lust incurred. Bronzino’s famous London Allegory incorporates a cautionary tale into his commentary on love, lust, gender, and human frailty. Hunched behind Eros is a tormented, green-tinged, and contorted woman identified as a syphilitic allegory of dolor or pain that was the perilous fruit of the unwise pursuit of physical pleasure.

Similarly, Luca Giordano’s Allegory of Youth Tempted by the Vices introduces us to the scourge of syphilis in the person of the male in the left foreground who exhibits the patterned hair loss, discolorations, and physical deformities of the advanced syphilitic as one of the terrible rewards due the youth who makes poor choices between the virtuous and the sinful. Cellini’s sparkling prose and these powerful images reinforced the widespread nature of the incapacitating disease and remind us that artists and patrons alike bore the scars of the Mal Franzoso and worried together about the impact this scourge might have on Europe writ large.

The recently discovered and colonized New World was an endless source of fascination for sixteenth-century Europeans. Eventually, their passionate interest in America’s oddities began to reveal the increasing benefits open to those who chose to study the new land than ravage it. Images of America by Jacopo Stradano and Orazio Farinati were among the first images of the New World that sought to characterize the encounter between Europe and America as an exchange. This exchange may have remained patently unequal but, for Renaissance Italians, America had something to offer Europe. Among the things that Stradano surely understood as a benefit to Europe (in addition to the hammock on which his America lounges!) was a new-found natural treatment for syphilis. As his contemporary, Girolamo Fracastoro, wrote in his ground-breaking poem on the disease, the Native American seemed to suffer less from the affliction and even appeared to contract fewer cases. Although this effect has now been attributed to the fact that the illness in America was somewhat different in form than the syphilis that infected Europeans starting in the late 1400s, Fracastoro learned from friends familiar with Native herbal lore about a wood, guaiacum, which could be reduced to a bark tea and provided the Natives with relief from syphilitic symptoms. Stradano’s series of engravings featured the introduction of guaiacum officinale as a pharmacological treatment for syphilis and one that had proved beneficial to another artist in the Florentine orbit, Cellini.

The famous Veronese physician, Girolamo Fracastoro, left a collected body of letters, poems, and essays that runs the gamut from his seminal poem Syphilis to a study on the Inundation of the Nile.[1] First and foremost, however, Fracastoro has been recognized as the chief proponent of a theory of contagion based on seeds, which is generally understood as the prototype for modern epidemiology.[2] The widespread association between doctor and specific venereal disease is confirmed by his appearance in an engraving produced by Jan Sadeler some fifty years after his death in Germany, where the learned doctor acts as the spokesperson for personal hygiene in a reiteration of the general social warning against the indiscriminate dalliances of young men and wanton women. Fracastoro lectured in natural philosophy at Padua in 1507. His researches ranged from medicinal simples to the heliocentric universe. As a physician, he addressed astronomical and astrological issues, primarily interested in the action of occult forces on human health. Fracastoro’s broad range of interests reflects the influence of his friendship with a specific group of individuals with whom he shared ideas about the nature of humanity and its universe. The derivative atomism of his contagion theory owed a great deal to the recent printing of Lucretius’ De rerum naturam, which had been edited by his fellow student and correspondent, Andrea Navagero. The intricate weave of medical theory, astronomy, and physics under the rubric of natural philosophy allowed Fracastoro to digest information of all sorts, some coming in the form of letters and manuscripts, some coming in debates and discussions with his erudite circle of friends in cosmopolitan Venice and academic Padua, but most delicious were the long afternoons of divine conversations shared in the superlative ease of their country retreats.

With the closing of the Universities of Treviso and Vicenza in 1405 by the Venetian government, Padua would become La Serenissima’s University, and her nobles and cittadini were “forbidden” to attend other universities or accept degrees from other institutions. In the academic setting of the University, the philosophical tradition in Padua sponsored debate about the merits of “experience” for knowledge of the natural world.[3] For physicians and botanists, the study of living or preserved plant specimens supplemented the lectures on Avicenna’s Book II, Galen, Rhazes and Dioscorides.[4] For medicine, “experience” led to the dissection of cadavers for the study of anatomy and physiology. The inability of theory to explain the workings of the human body was indubitably expressed by Galen:

I would like to teach you in as few words as possible that empiricism suffices to discover all means and methods of healing. Nobody, I say, who investigates natural things, knows sufficient about the practice of medicine, if he does not make use of experience.[5]

In any event, graduates of the University like Girolamo Fracastoro found themselves in the thick of debate about medical practice in a circle of nobles and wealthy cittadini that shared meals, thoughts, and poems about nature, human nature, and human health.

One of the remarkable and less well understood features of early modern medicine is the presence of occult forces, both celestial and terrestrial, at work in the arena of contemporary health care. Some insight into the pervasive nature of such unseen influences comes from a study of other investigations of the natural world that praised or pondered these mysterious movers. Among such works is the Ten Days in the Villa of Agostino Gallo from 1560. After Gallo previewed the “calendar” of a restful respite at his country estate, Le dieci giornate presents two poems: “Del selvaggio academico occolto” and “Dell’oscuro academico occolto.” To the surprise of the reader, the text was not only the observations of two men strolling in a villa near Brescia but also an introduction to serious study in God’s university. Gallo, according to the poem, has come to the realization that his classical sources on agriculture and country life were inadequate; thus, he set out on a mission (“jousting,” he says, with his ancient Roman counterparts) to bring to light for Italy many things concealed from Varro, Palladio, and Columella.[6] With Heaven and Earth his friends, he awakened “thousands of sleeping, slothful geniuses” to teach us of the “vero culto de la terra.” For Gallo, villa life was “fortunate” and free from “fleecing by soulless lawyers and Procurators tangled in indiscretion,” “joyful” because there you will see “the dance of the sheep” and “the leaps of the goats,” and “soft” with the “sweet conversation of friends” thanks to the “sacred profession of the farmers.”[7] This “santa professione” was the foundation of on the new culture of noble agriculture in the Cinquecento Veneto.

At the point in his Dieci Giornate at which Gallo defined farming as a “sacred pursuit,” he attacked alchemy or false “magic,” defaming the entire practice and espousing hope that the “miserable fools” who practiced alchemy on precious metals would “come…to be poor as they ought to.” However, one subset of alchemists earned Gallo’s praise: farmers. According to Gallo, “blessed are those if they give up such blindness and occupy themselves in this true alchemy of agriculture, bringing much pleasure to God and to the whole world, for it is hurtful to none and useful to all.”[8] His words echoed Ficino’s claim that the farmer, who makes fields ready for “gifts from heaven” and uses grafting to transform plants into “new and better species,” was a noteworthy practitioner of “natural magic.”[9] Several years earlier, Alvise Cornaro had specifically defined agriculture as “true alchemy,” paving the way for Gallo’s pointed contrast between good and bad alchemy. The idea of the farmer as a kind of magus, alchemist, or scientist clearly fascinated Gallo and proponents of Santa Agricoltura and inspired wealthy patrons to throw their support behind agriculture and embrace the “holy profession” of scientific farming.

Girolamo Fracastoro was the owner of a villa outside Verona, where he hosted the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and spent his days in a pleasurable mix of scholarly research and comfortable retreat.[10] The easy freedom with which he maneuvered in the perplexing currents of medicine, astronomy, and natural and moral philosophy while dabbling in theories of poetics, collecting and cultivating new species of plants, and debating the merits of the latest discoveries from the New World suggests that his education at the Studia and University of Padua provided him with a thorough background in the sciences and the humanities. Similarly, he appears to have relished his absorption in the lively and ongoing debates that marked the Veneto’s intellectual center. His appeal certainly resides in his willingness to offer an opinion about anything of interest to a companion or a reader.

In his pioneering De contagionibus, Fracastoro described the death of his friend, Andrea Navagero, of a “truly pestilential” fever, typhus, that he characterized by “red spots and some also of purple, similar to the punctures of fleas.” Andrea Navagero, dying in France in 1529 as ambassador to the king of France so not a patient of Fracastoro’s, was one of the first deaths attributed to the dreaded disease.[11] Navagero’s untimely death deprived Venice of her state historian and foremost botanical collector. Fortunately for garden history, the ambassador had inspired similar interests in his close circle of friends, and Ramusio and Fracastoro would later cultivate or distribute specimens received from Navagero and other travelers. One of these sources was Gonzales Ferdinando d’Oviedo.

Oviedo’s History of the Indies might be his best-known contribution to early American studies, but through his contact with Fracastoro, Oviedo’s research and transmission of knowledge about American medicine directly contributed to the Cinquecento study of syphilis treatment.

The early epidemiologist Fracastoro came by his knowledge of America and its native medicine first-hand. He was among a group of Italian intellectuals who had become friends with Fernando Gonzalo de Oviedo during his travels in Italy in the early years of the century. Oviedo was later the Spanish governor general of Hispaniola, a partner with Giambattista Ramusio in an investment enterprise in Caribbean sugar cane that hoped to bring American sugar to Europe, and the author of the first major history of the Spanish discoveries. Although his Historia Naturale has been characterized as a rather harsh assessment of the natives, Oviedo’s reports of the bounty of America the continent and his interest in the strange and wonderful flora and fauna found in the New World reveal his background in natural philosophy and empirical or observational science. The dedicated focus on the aspects of American life and features of the New World places Oviedo’s study in the realm of science rather than simple reportage or chorography. This more scientific interest echoed the mentalite of the famous physician Fracastoro and the increasingly renowned geographer Ramusio. In turn, one can begin to see the circulation of Oviedo’s manuscript to these gentlemen prior to its publication in a translation produced by their close friend Andrea Navagero, shortly before his death in 1530, as both a clear sign of their intellectual curiosity and a conscious decision by men like Ramusio and Fracastoro to remain open to an understanding of America as a terra incognita that was slowly revealing itself as a positive influence on European society.

Many desperate sufferers of the deadly venereal disease resorted to mercury treatments. Benedetti, who prescribed this therapy, warned of the potential harm to teeth while Massa urged his Venetian clients to try alternative diets before taking mercury. In any event, no treatment seemed to consistently defeat the stubborn, widespread, and painful disease. Into the breach slipped word of a silver bullet, a medicine derived from the guaiacum tree and used widely by native Americans to treat their apparently less vicious and quite tolerable syphilitic symptoms. Francesco Guicciardini does not name this cure, although he notes the use of the new world treatment and his widely read discussion of the French sickness indicates that he and his contemporary Italian readers apparently accepted the fact that God, quite sensibly I should say, provided an antidote to the scourge in the form of a tree whose juice, when imbibed, saved the infected from the agony of syphilis. The best description of this “holy wood” was composed by Oviedo some time before 1526 and later included in his Summary of the Natural and General History of the West Indies, printed in Italian in Venice in 1534 and included in the first edition of the third volume of Giambattista Ramusio’s Navigazioni e Viaggi in 1556.[12] Mercury treatment and other occult remedies paled before this botanical remedy, guaiacum or palo santo, native to Hispaniola and the salvation of the indigenous population. In the wake of Oviedo’s first-person account of the lesser suffering of Amerindians from the disease and the positive effects Guaiacum treatments offered, Fracastoro and other Italian physicians instituted an increasingly widespread use of this curative bark concoction. By mid-century a number of hospitals treated all patients with the “holy wood,” and physicians and government officials gave high marks to its successful remediation of pain and suffering. Although no modern evaluations indicate benefits from the use of guaiacum derivatives in the treatment of syphilis, it remains a popular natural treatment for inflammation and skin irritation. Quite likely, guaiacum and isolation helped in the restriction of the spread of the disease during the years that herd immunities and resistance developed in the white, European population. Furthermore, the adverse effects of mercury treatments were essentially eliminated for those patients treated with guaiacum. In any event, Oviedo and Fracastoro mark an early point in the exercise of learning from the Americas and their indigenous peoples in the wake of the early contact, colonization, and exploitation of the new world and its population.

In conclusion, the devastating Pox gave Europeans a quite painful incentive to consider their place in the expanding world. Girolamo Fracastoro offers us a case of the particularly receptive and inquisitive early modern Venetian physician whose work involved the identification and classification of disease, research into the very nature of epidemic contagious disease, and the search for new alternative treatments. Both mercury and Lignum vita treatments for syphilis came to Italy from abroad, but the care with which Fracastoro and others reviewed the relationship between the typical prescription of quicksilver espoused in Avicenna and other Muslim authorities and the New World treatment for the new disease described by his Spanish colleague, Oviedo, reveals the idiosyncratic willingness of members of the Venetian elite to step back and take hard looks at what America delivered to Europe both for good and for ill. Oviedo’s work was not truly groundbreaking itself, as his text echoed contemporary writings on botanical subjects produced in Italy, citing Pliny and Avicenna, for example, early in the second book of hisHistory of the Indiesabout the habitable torrid zones and the misinformation or confusion produced by the reading of the available natural philosophy treatises. Oviedo does parenthetically applaud Avicenna, who “wrote and said better…than any others that wrote” on the same subject.[13]Furthermore, Oviedo does not help his reader understand the disease or contagion, but his work and career link Navagero and Italian humanism to the identification of new diseases and new species, subjects of paramount importance in Venice and at the University of Padua and to their mutual friends and colleagues like Ramusio and Fracastoro. In the end, Oviedo’s history delivered new ideas to Fracastoro and others who navigated the complex world of scientific and medical research in the early modern Veneto and must be recognized for focusing our attention on the arrival of New World treatments in Europe and the means through which knowledge of these discoveries was transmitted and introduced into the pharmacies of Venice and Verona by Fracastoro and his circle.

Notes

[1] E. Peruzzi, “Gerolamo Fracastoro,” DBI 49 (1997): 544; “Discorso di messer Gio. Battista Ramusio sopra il crescer del fiume Nilo, allo eccellentissimo messer Ieronimo Fracastoro,” in Navigazioni e viaggi, Marica Milanesi, ed. 6 vols. (Turin: Einuadi, 1978), vol. 2, 410-11.

[2] Vivian Nutton, “The Seeds of Disease: An Explanation of Contagion and Infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance,” Medical History 27 (1983): 22. Girolamo Fracastoro, De sympathia et antipathia liber unus, De contagione et coagiosis morbis et eorum curatione libri tres (Venice: Giunta, 1546); Alcon sive de cura canum venaticorum, was included in H. Fracastorii poemata omnia (Padua: J. Cominus, 1718).

[3] “For three centuries the natural philosophers of the school of Padua, in fruitful commerce with the physicians of its medical faculty, devoted themselves to criticizing and expanding this conception and method, and to grounding it firmly in the careful analysis of experience.” Randall, 178.

[4] Reeds considered Rudolph Agricola and Ermolao Barbaro to have seen quite early the value of an “investigation of nature,” citing Barbaro’s 1484 description of his daily routine in Padua to justify her argument that “contemplating” herbs was becoming part and parcel of the emending of classical botanical treatises. Reeds, 27.

[5] Galen, On Medical Experience, R. Walzer, ed. and trans. (Oxford, 1944), para. 31. Cited in Rosenthal, 191.

[6] Ibid., 205.

[7] Gallo, 205.

[8] Ibid., 214: “questi miseri insensati si veggono essere divenuti poveri da dovero….beati loro si in cambio di tale cecità, si occupassero in questa vera alchimia dell’agricoltura, la quale tanto piace a Dio, & a tutto il mondo, poiche massimamente non nuoce a niuno, e giova a tutti.”

[9] Copenhaver, 1988, 274 cites Ficino’s De vita coelitus comparanda, 1576, vol. I, 570. Ficino described “nature as a magician” and explained that the farmer “who prepares his field and seeds for gifts from heaven and uses various grafts to prolong life in his plant and change it to a new and better species” offers an example for the philosopher “whom we are wont rightly to call a magician.” (Copenhaver, trans.) Although Ficino does not state explicitly that farming is natural magic, the parallel between the natural philosopher and the farmer may have provided impetus to Gallo, Cornaro and others interested in the “true alchemy” of agriculture.

[10] E. Peruzzi, “Gerolamo Fracastoro,” DBI 49 (1997): 544; “Discorso di messer Gio. Battista Ramusio sopra il crescer del fiume Nilo, allo eccellentissimo messer Ieronimo Fracastoro,” in Navigazioni e viaggi, Marica Milanesi, ed. 6 vols. (Turin: Einuadi, 1978), vol. 2, 410-11.

[11] Bonuzzi, Op cit., p. 428.

[12] The publication history of Oviedo’s work appears in the introduction by Marica Milanesi to his Sommario in Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Navigazioni e Viaggi, Turin: Giulio Einaudi, 1985, Vol. 5, p. 210.

[13] Ibid., p. 357.

Copyright © 2021 by Association of Graduate Liberal Studies Programs