from the editor

Ghosts

Memory is a funny thing. Each of us, no matter how old we may be, has a certain store of memories that are immeasurably precious to us. We hold these memories tightly, finding the best, most secure place to house them in our minds or our hearts or wherever it may be that our memories ‘live.’ We visit the places and people remembered, sometimes we even try to lose ourselves in them in an attempt to return some semblance of reality to that which is remembered; to feel as if we are there again presently, or at least to remember what it felt like when we were there. Our memories can be a comfort, even if that which is remembered, by its absence, is painful; at least by remembering we may remind ourselves of what once was and rekindle a degree of warmth from a once bright radiance now diminished by temporal distance. In his essay “Shadow Cities,” André Aciman recounts his own attempts to locate his remembered Alexandria home in his latter New York home through repeated visits to Straus Park: “[h]ere I would come to remember not so much the beauty of the past as the beauty of remembering.” We want the past, or at least some of the people or places from the past, to come back to us or to allow us to return to them. But the best we can ever really achieve is to haunt the spectral renderings that we take to be faithful depictions of what’s been lost; or allow them to haunt us.

A few months ago I rode east for a few hours in search of ghosts. It was a Saturday in late spring; I was riding a 50-year-old motorcycle 35 years into the past, to the camp where I had spent so much time—so much meaningful time—as a teenager. A beautiful sunny day is reason enough to throw a bag on the bike and go, but this particular destination was one that I’d had in mind for a while. Yet despite the months I’d spent lingering over the idea of this visit, and the weeks that had passed since I’d made up my mind to go, I don’t think I can say what it was exactly that I was looking for or what I thought I’d find.

After a few hours spent on roads winding down from my mountains, I finally passed through the tiny old city outside of which the camp had been founded. As I rode the two-lane Pike though the sleepy town of B–––, riding alongside pastures and fields, I suddenly remembered it all: sitting anxious in the back seat as we diagonally crossed the railroad tracks just past the edge of town, passing the lime kiln and the smell of cows, wishing for the last mile to disappear into the rough single-lane and the distant top of a cupola behind the trees on the hill. Now here I was cresting that last hill again, following the bend in the road to the right and then back again to the left, finally entering the last tree-lined stretch to the foot of the stairs of the main building: a nearly 300-year-old house dwarfed by the hulking attached boarding school dormitory that was built near the end of the nineteenth century.

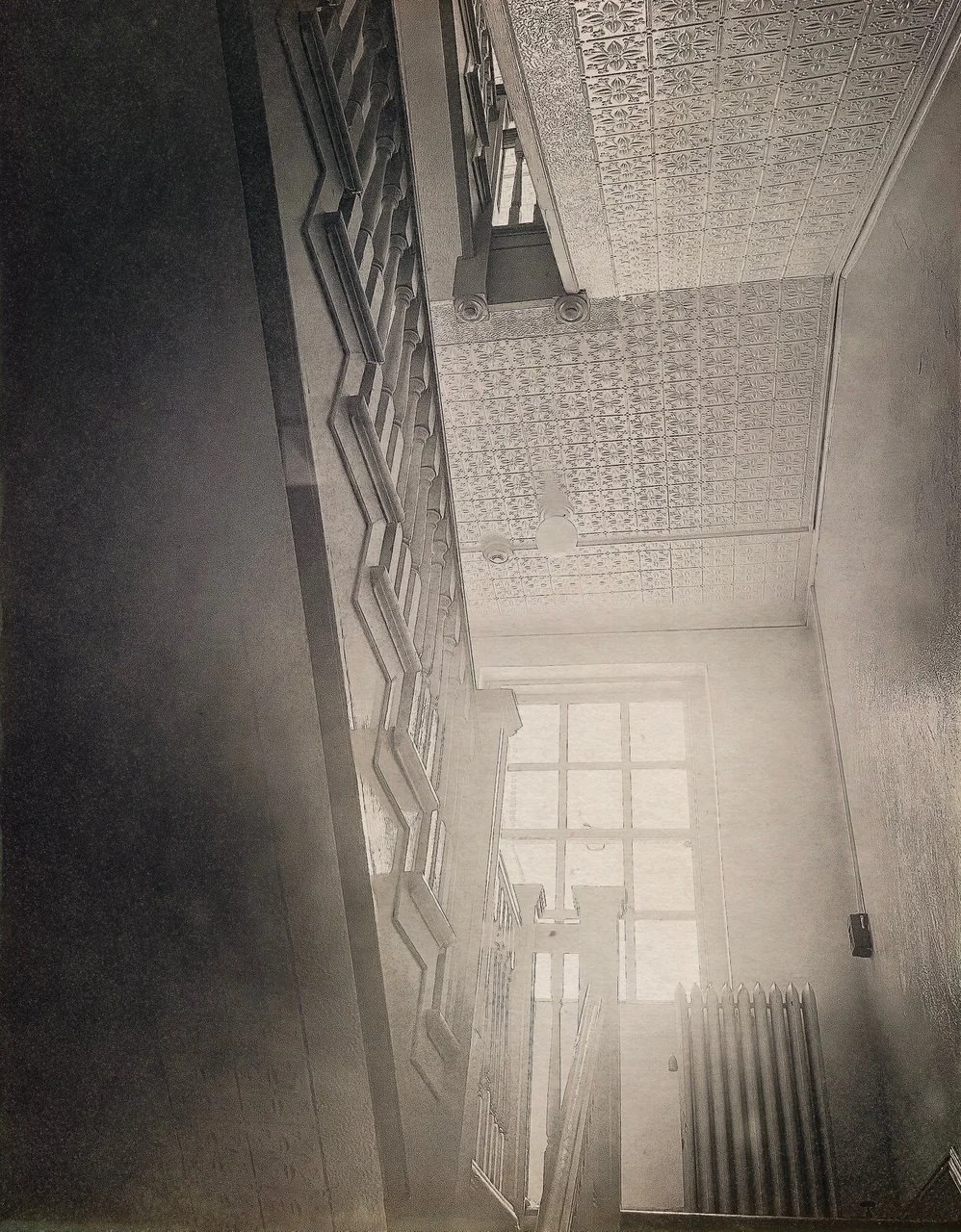

I parked my bike on the lane in front of the building, then just stood and stared, amazed at how it all seemed to look the same—the concrete stairs to the covered porch, three stories of red brick, a bumped out wing on either side, and a white, windowed cupola at the top, piercing the blue sky above. I walked around to the back of the building, frequently gazing up at the tall windows in the brick façade, empty save for the old white muntins with peeling paint. At the back of the building I tried the door that led into the original farmhouse, the oldest portion of the building, and was only half surprised to find it unlocked. Knowing that I probably shouldn't, unsure of what (if anything) might happen if I were caught trespassing, I quietly ventured in. And everything was as it had been so long ago: the old oak stairs with the carved balustrade, leading up to the bedrooms centuries removed from their original inhabitants; the wood-framed, poorly upholstered matching chairs and sofa spread across the stained and lumpy grey carpet of a small group meeting room; the garden tools and old black-and-white and sepia photos on the walls; the tin ceiling covering the larger staircase that leads up to the dorms and down to the kitchen and cafeteria; painted, chipped radiators sitting lifeless on ceramic tiles or old wood planks, under windows too old or heavy to open any longer. All of it, exactly as it had been all those years ago; or maybe it was merely exactly as I, in this moment, seemed to remember how it had been, back then.

There is now a modern conference center here, which I have no recollection of ever having visited but which looks eerily familiar. I remember seeing it once in a dream, and for a moment I’m struck by this realization; am I remembering a dream that I once had about how a place from my past may look now? How did I know that this would be here? But I’m unsure whether I actually had that dream, and I can’t say with certainty that I hadn’t ever visited this place in all the years between then and now. Maybe I had visited, and despite my not remembering there are somehow flashes and glimpses of things I would have seen on that visit with nothing to ground them for me in fact or memory. Maybe the dream that I had, which I do seem to remember having, is actually just the memory itself; or maybe it really was a dream, but simply a dream in which I remembered rather than a dream in which I imagined. We trust our memories to be precisely that—accurate scenes, true worlds, preserved forever in the exact form and fashion in which we originally experienced them. Wandering through the rooms, climbing stairs, gazing through windows, I was certain of the correspondence between what I was seeing, now, and what I was remembering. Or maybe, as Aciman offered, perhaps I was just moved not by the memories but rather by the remembering.

We always believed that this place was haunted. There were so many wonderful stories, probably all adapted from some other stories that someone else had heard from another place or another time or simply made up. Back then, though, I was sure that the stories, or something like them, were true. There were places in this building where I would not go, even in the middle of the day; I never wanted to enter the dorms alone, or be the last person awake at night in the dark. Now I know that this place surely is haunted, but the ghosts that I now know to be here are very different from what I had imagined back then. Seeing the exact spot on the stairs where I had my first real kiss; finding a drawing I’d done back then, signed and dated in my own hand and date, still hanging on the wall in the library with drawings made by my friends; standing in the places where I had shared, cried, danced, loved. I can’t see the ghosts, but I know that they are here, all around me; I know that one of those ghosts is me.

I wonder whether a place can have memories. I wonder whether this place has memories of me, my friends, all us for whom this place was so meaningful. Surely the place can see our names and our drawings on the library wall; is that the same thing as remembering?

* * *

Many before me have lamented the sad fact that we so often do not know when a particular time will be the last time. Because of a series of poor decisions made by seventeen-year-old me, I was not allowed to attend for what would have been my senior summer here. I never got to have my ‘last summer’ at this camp, thus I did not face each unfolding moment there in the knowledge that each could be the last … something. We often think that it would be good to know when we are near the end, when we’re in the final moment(s) of something, to be able to make the most of the moment—the last time: to say all that we want to say, to take in every detail and fully feel every sensation, to etch all of it, perfectly and permanently, into our memory. But a strong case can also be made for not knowing, instead being able to simply be in the moment, as you’ve always done, and enjoy it—authentically, unreflectively, without sadness. I suspect that, whatever our rational brains may tell us, we are more often better off not knowing, if only to postpone sadness, or pain, or loss a little longer and preserve the possibility that the final memory may largely be a happy one.

As we get older, it’s natural to think more and more about the comparative value of knowing or not when things are coming to an end and to wonder how many such ‘final’ times have slipped past without our knowing. We ask ourselves after holidays, after visiting our aging parents or hosting our adult children, after time spent with old friends or time spent alone in a particularly blissful way, after we say ‘I love you’ or ‘goodbye’; will that be the last time?

This moment for me now, as I write these words, is not a moment in which I must wonder, because I know—the present issue of Confluence will be my last as Editor. For ten years I have had the great privilege of sharing some truly excellent work from a multitude of writers and educators, while also sharing occasional words of my own. Everyone—past and present AGLSP board members and administrative staff, the editorial board and reviewers who read, critiqued, and improved the manuscripts we received, the contributors who generously submitted their work, and everyone who has read even a word from our pages—has played an immensely important role in the success of the Journal and in my enjoyment of my time at the helm; I am truly grateful to each of you. Yet I also believe that it’s now time for a new voice for the Journal, and I’m excited to see what will be next.

As I thought about how I might close my time as Editor, one of my favorite scenes from Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou kept coming to mind. At the end of the film, an exhausted, beaten, heartbroken Steve Zissou sits in his tiny observation submarine, surrounded by everyone—his mutinous crew, his estranged ex-wife, his chief professional rival, his former financier, and the ‘bank stooge’ who was sent to undermine his projects. But really he is surrounded by the people who support him, who love him, while he tries one final time to find the creature that killed his best friend. Together, Zissou and his companions stare into the black abyss of the deep sea, startled and awed as a school of glowing pink fish swim directly at them from ahead and then surround the tiny vessel. Just as the small craft settles in the wake of the passing school, the first notes of Sigur Rós’ “Starálfur” play and the monstrous, magnificent jaguar shark winds its way from the distance straight at the defenseless craft, nearly a perfect symbol of vulnerability. Jaws drop and hands cover mouths as, utterly defenseless, they all sit in fear and awe at the gigantic creature—all except for Zissou. His hate and his anger—all of the feelings that had fed his ambition and defined his purpose—dissipate, dissolving finally into a blend of satisfaction at having proven this mythical creature exists and resignation at the fact that he would do nothing further: he would not avenge his friend, he would not kill the creature, he probably would not make a lasting mark. And then sadness, in the immediate, unmediated experience of a ‘final time.’ In this moment there is no possible resolution, no further questions to be asked, no answers to be found. All that is left is for Zissou to say, perhaps to himself or perhaps to the others, “I wonder if it remembers me.” And then it’s time to go home.