Peter Lloyd Jones earned a BA in Fine Art at the University of South Florida and a BID in Industrial Design at Syracuse University. He is a member of the North American Sartre Society, with which he has presented a dozen papers at peer-reviewed conferences at universities. His juried paper “Sartre’s Concept of Freedom(s)” was published in the journal Sartre Studies International, Vol. 21, No. 2. As a mainstream journalist, he has written for numerous motorcycle publications, and after 30 years his contributions are still being published in print and online, as Teller of Tales, at RoadRUNNER magazine. His book The Bad Editor is a self-published collection of his journalistic contributions.

Albert Camus, The Impatient Nostalgist in North America

Peter Lloyd Jones, Lindenwood University

We are the places our lives pass through, changing us, a condition Albert Camus eagerly embraced. A glance through his writings reveals the sense of place Camus carried within him: the classical ruins at Tipasa and Djemila, Oran, Algiers, the sea… maybe mostly the sea. America?

Albert Camus visited North America, in 1946, for a two-month stay on assignment for the Provisional Government of the French Republic, and to promote his first novel, The Stranger, which was about to be released in English, in America. This puzzling novel resonates the absurdity of life which Camus had presented in his philosophical treatise, The Myth of Sisyphus. Camus wrote in his review of Sartre’s novel, Nausea, “A novel is never anything but a philosophy expressed in images.”[1]

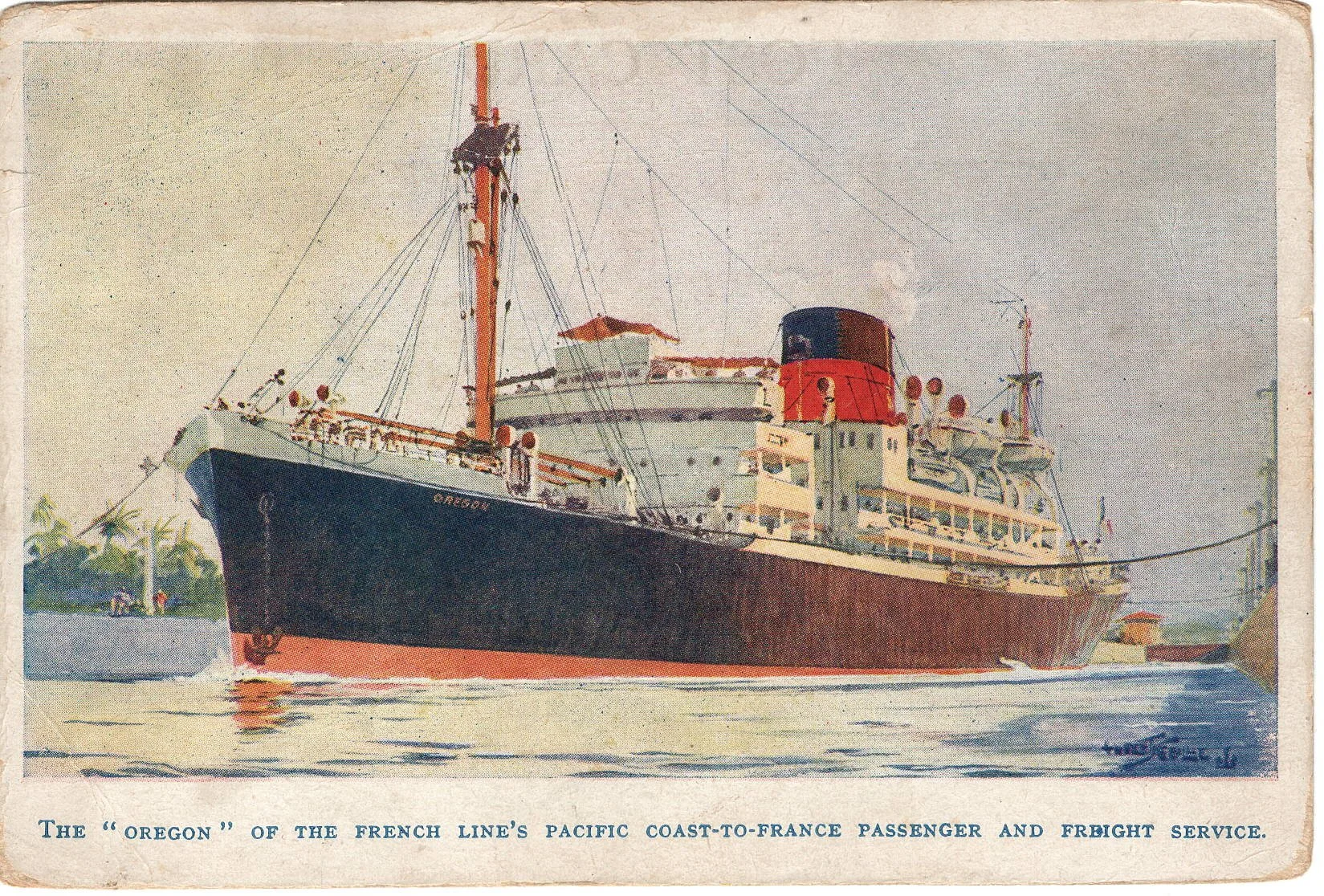

Camus crossed from Le Havre, France, leaving March 10 on the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique French Line, M/V Orégon. Upon seeing the ship, Camus disappointingly discovered it to be a freighter, not an ocean liner, with barely three dozen cabins for passengers. Camus next discovered that his lodging for the two-week crossing would be as one of five in a room for four, its cramped size further compromised by a foldout bed between the lower bunks, one of which would be his. After an additional night’s stay on the Orégon in New York’s harbor, Camus stepped onto the Americas on March 25.

I wasn’t born until long after 1946, but learning of Camus’s visit to America—despite its exile of timing—brought him closer to me by proxy of place; closer as a once-breathing for-real fellow human, closer within his literature, closer emotionally.

M/V Orégon — postcard published by Imprimerie Crété à Corbeil, Paris, France. From the author’s personal collection.

On the third day of his stay, Camus met A. J. Liebling, an editor at The New Yorker magazine, who quickly authored a short piece about Camus’ visit that appeared in “The Talk of the Town” section of the April 20, 1946, issue. In that article, Liebling suggested that Camus’ writings describe life as grim, quoting Camus responding that “Just because you have pessimistic thoughts, you don’t have to act pessimistic. One has to pass the time somehow. Look at Don Juan.”[2]

Camus and Liebling became quick friends, each discovering the other’s risky role in wartime journalism: Liebling was a front-line reporter, whereas Camus was Editor at Combat, an underground paper published in Paris during the occupation. Camus had moved to Paris, in 1942, taking on editorship at Combat while common sense and hordes of others were fleeing France, while Liebling witnessed the war from Paris until 1940, then from the Allied lines in Camus’s Algeria, and to the beaches of D-Day before returning to the liberated rues of Paris. One might imagine the smiles these two shared after learning of each working in Paris as war-time journalists. Now, in New York City, a year and a half later, Camus found Liebling’s fluent French a welcoming invitation to an easy friendship.

Possibly adding force to their friendship might be a shared enthusiasm for unsettling lived satires. Numerous sources suggest that Camus and Liebling often engaged in bar-crawl adventures throughout Manhattan, searching out dive bars.

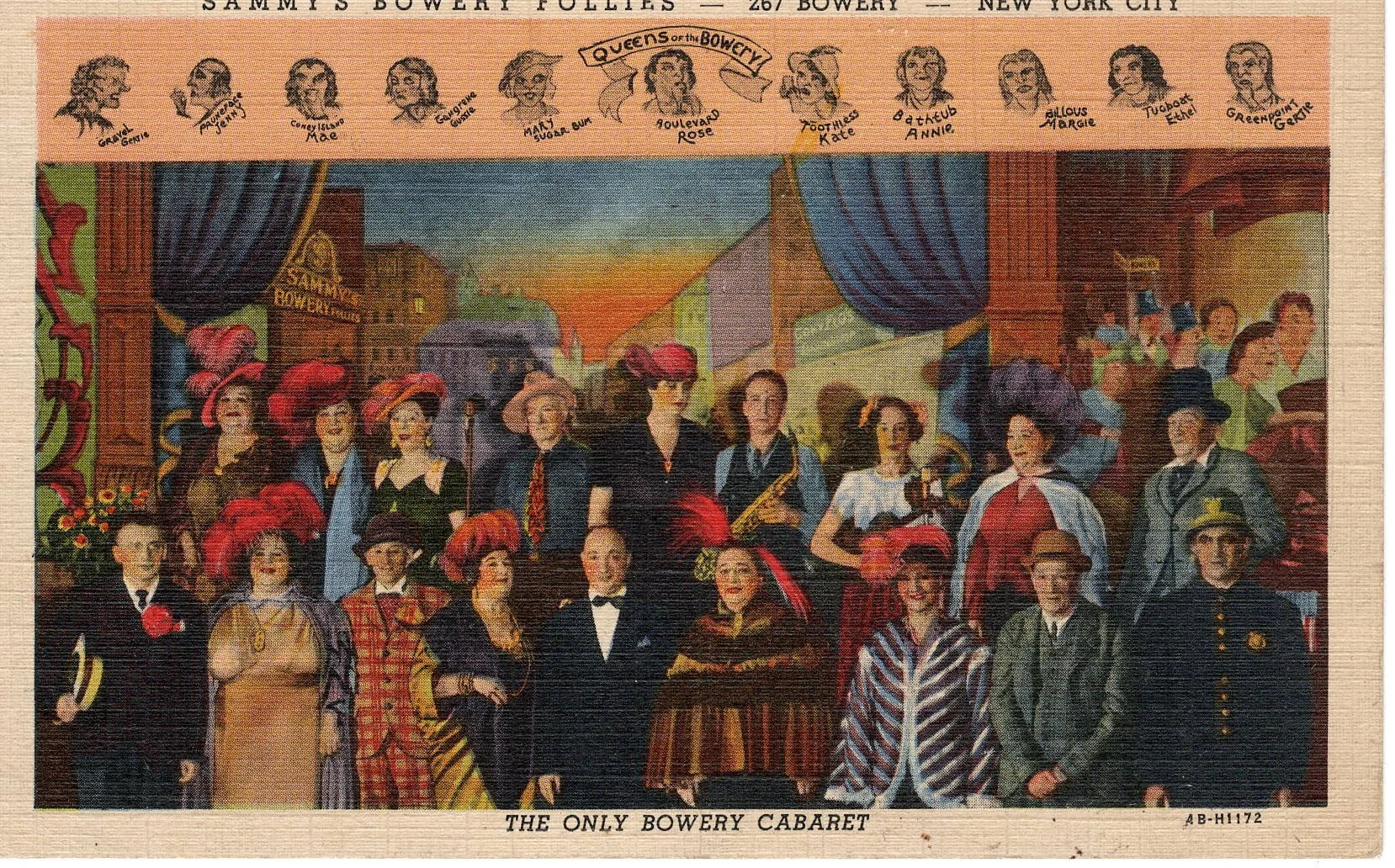

Once Camus discovered Sammy’s Bowery Follies, where the unfortunate and the fortunate shared drinks and dances, he was mesmerized, returning often to witness the absurd in action. Camus wrote in his journal: “A few paces from the half-mile-long stretch of bridal shops the forgotten men live. It is the gloomiest part of town, where you never see a woman, where one man in every three is drunk, and where in a strange bar, apparently straight out of a Western, fat old actresses sing about ruined lives and a mother’s love, stamping their feet to the rhythm and spasmodically shaking, to the bellowing from the bar, the parcels of shapeless flesh that age has covered them with.”[3]

Sammy’s Bowery Follies, the “only Bowery Cabaret” — postcard published by Curt Teich & Co., Chicago, IL. From the author’s personal collection.

Though famous for its colorful clientele of disenfranchised misfits, Sammy’s wasn’t a back-alley dive bar—it was a well-marketed, must-see, New York City attraction, where members of commerce mixed with the embers of society. In the 1940s Sammy’s was also frequented by photo-artist Weegee, capturing images of New York City’s underdogs and underworld where sadness and celebration sat just a row of empty glasses apart, and a good time and crime too casually crossed paths.

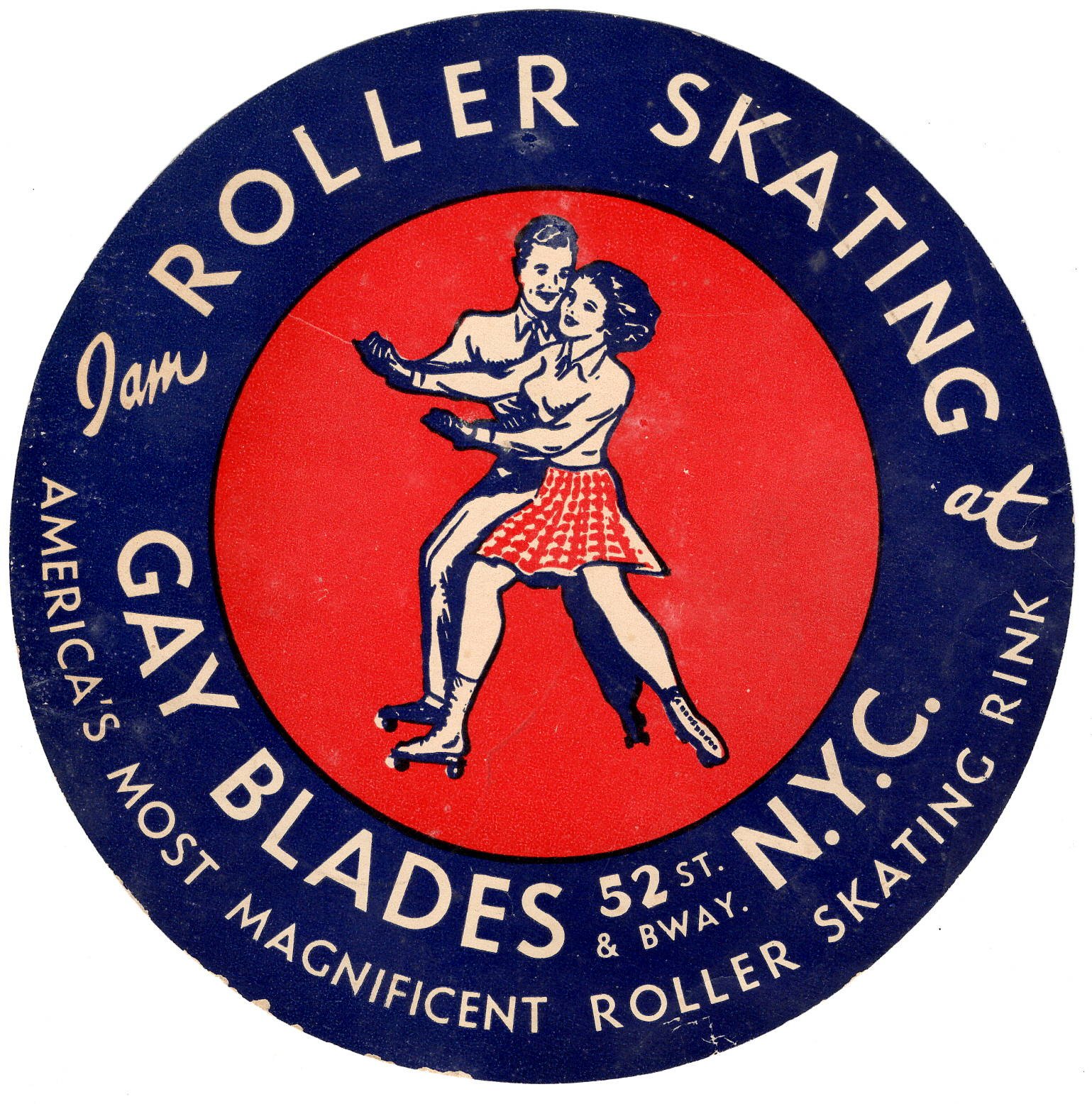

Gay Blades, NYC — advertisement image from the author’s personal collection.

Camus’ letters and notebooks also reveal other of his intrigues in New York. Bridal shops with sad-looking manikins in their windows, the smiling faces in advertisements, undertaker magazines, long-legged New York women, roller skating at Gay Blades, East Orange Public Library where only William James was listed in the Philosophy section, and ice cream, delicious ice cream.

Just over three weeks into his stay, Camus met Patricia Blake, a brilliant 20-year-old who, on top of her native English, spoke French and Russian, was well-read and knowledgeable about Russian history and its evolving politics, and with whom Camus became quickly and deeply enamored. She worked at Vogue magazine, soon meeting him for lunches and as many evenings as possible. On their shared outings, Camus obsessively took Blake to the Central Park Zoo’s Monkey House; Blake would later share that they’d visited it 20 times or more in eight weeks.[4]

At the time of his visit in 1946, Camus, at 32 years old, found that American women often compared him to Humphrey Bogart. As a hero of “The Resistance,” an absurdist, a humanist, a novelist, and a cigarette-toking pied noir, Camus was a hot property, and he knew it. On top of that, his newly translated novel, The Stranger, was about to hit the streets, to disturb and enrapture a continent.

The Stranger’s perplexing and puzzling story is impossible to turn away from. On the surface it tells a tale about Meursault, a likeable ontological sociopath who doesn’t seem to care about anything or take responsibility for his actions. He doesn’t display emotions when his mother dies, immediately has sex with a woman he has just met, who quickly loves him, then buddies up with a pimp and shoots an Arab to death because…? Then he shoots the Arab’s corpse four more times.

The novel’s second part is Meursault’s pretrial days in jail, his trial, conviction, and sentencing to the guillotine. The novel ends with Meursault hoping for a large crowd jeering him with cries of hate at his execution, to make him feel less alone. Maybe what’s most disturbing about the novel is that Meursault doesn’t seem odd enough to us. Does he simply act on thoughts most have but let pass by?

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus considers how, in the silence that answers supplications to the heavens, life is absurd. In response to that silence, Camus asks, is suicide a reasonable option? If there is no meaning to existence, is there reason to exist? He answers with the thought that, even if life is absent inherent meaning, what is won by being dead? It’s sort of Pascal’s wager in reverse; without faith in God, not killing oneself provides options.

The absurd is the tying theme of these works—one of art, the other of philosophy. It’s an absurd that results from man’s need for meaning in a universe that supplies none. An absurd of unanswered prayers.

I’ve long admired Camus’ artistic abilities and philosophical challenges, although his arguments are more lyrical than logical. But until midlife—until I started reading Herbert R. Lottman’s Albert Camus a Biography, the source for much of what I say here about Camus in New York—I had no idea that Camus had walked into my world. I also hadn’t suspected that his visiting America might matter to me.

And it does matter to me. It also matters to many others, such as Liebling and others who met him. It matters also to Americans who have only read his writings. In reaching for connection with others from different times and places, we concede our failures to capture the past. That redoubles our empathy for place, which often is within reach. And Camus reaches back to us through his feelings for the meaning of place. There’s a theme of separation in many of Camus’ writings, a melancholic nostalgia for everything he loved that was out of reach. “I have my ideas about other cities—but about New York only these powerful and fleeting emotions, a nostalgia that grows impatient, and moments of anguish.”[5]

When we seek the places of literature it’s often confused by the impossibility of discerning the real from the invented. Also, when searching for an author’s antecedents, are we looking for the author or the author’s inspirations? Novels are true and untrue, with a veil obscuring where fact ends and fiction begins. Is it any of our business to parse through that? What can we do if it’s a science-fiction writer with whom we seek community? We will not find Ray Bradbury on Mars.

Prior to my discovery that Camus had visited New York, he and his writings existed in places impossibly distant from me, in both time and space. He didn’t seem of the material world I occupy. The foreign lands in which his tales exist were antecedents beyond the reach of my empathy. Maybe humans are wired in such a way that the people and places we haven’t personally experienced are forever a bit fictional to us, even if they are, in fact, factual. Maybe tangibly touching a texture, smelling an odor, feeling the warmth of a different place’s sun, are required for truly knowing. So we reach for places that might bring us closer, visiting in masses the sites of great battles and in solitude the graves of who we’ve loved.

I hadn’t previously found value in seeking the footprints left by a writer. I hadn’t thought abstract concepts require material locales. We had no Arabs in my neighborhood, no pied noir, no sun-bleached beaches once ruled by Romans and Moors. So what? The concept of Camus’ absurd is comprehensible anyway.

Yet I was stunned to find myself thrilled at learning from Lottman that Camus had visited New York, my home state. I was surprised at my hunger for physical empathy with Camus, as I traveled to New York City to seek out what I might find currently of where Camus once walked.

Unfortunately, Central Park’s Monkey House was demolished in the 1980s. But what remains is the streamlined Century Apartment building on Central Park West, where Camus stayed for much of his visit. From the street, though, it’s a cold building without any tangible Camus-slept-here magic. The drug store where Camus breakfasted in the building’s northeast corner has been innumerous businesses since 1946.

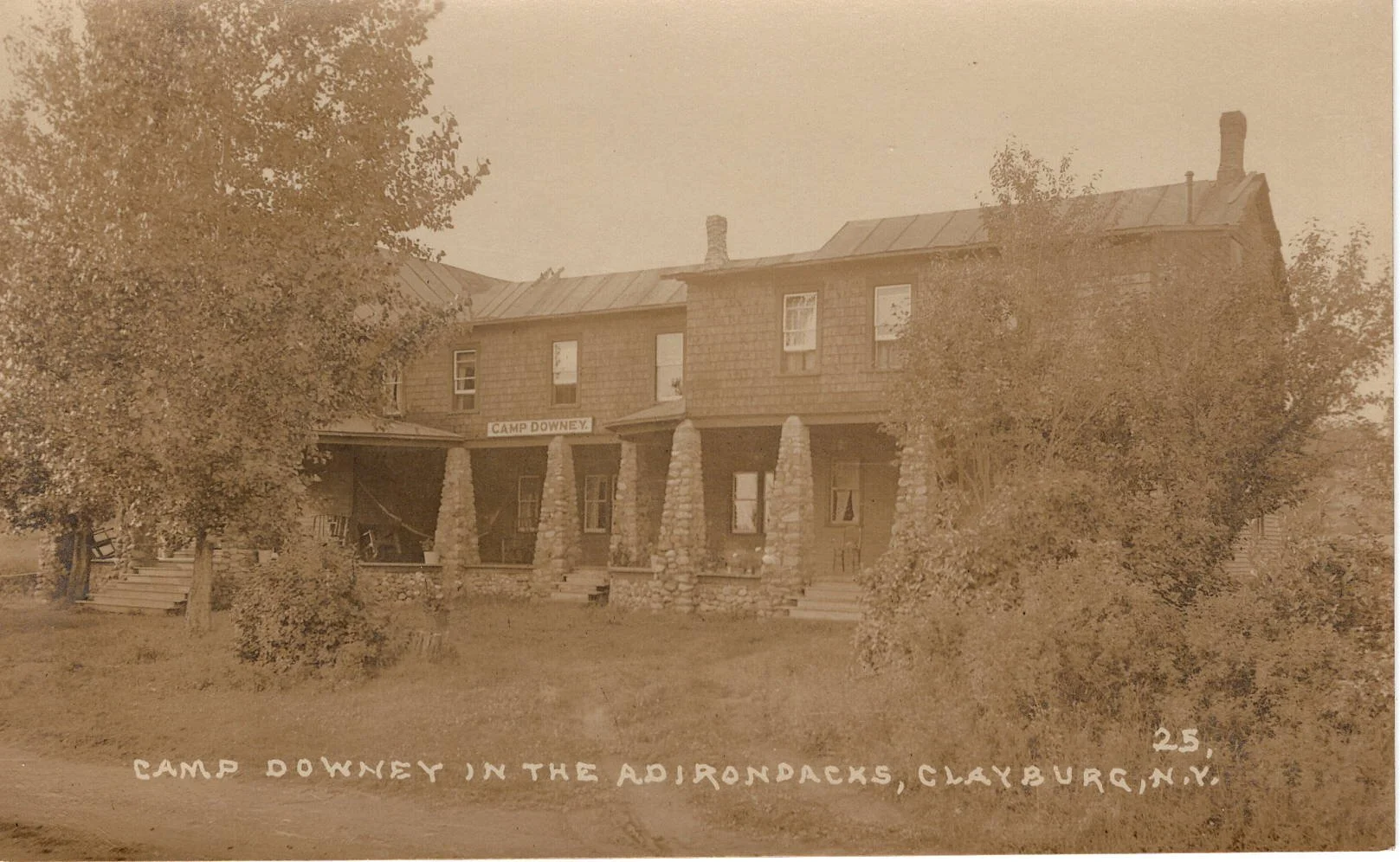

What stood out most to me was Lottman’s mention of Camus’s travel by car from New York City to Montreal, Canada, during which he and the driver spent a night in the Adirondack Mountains at Camp Downey, in the village of Clayburg. This jumped out at me with brighter promise than any site in New York City because I am from Central New York State, a short drive from the Adirondacks. I had spent time in the Adirondacks as a child, as a teenager, and as an adult. On his drive north, Camus rolled right into my own “neighborhood.” I also wondered—would a lone site in the country have an inherent intimacy missing from the streets of New York City?

I was excited to discover that Camus’ American Journals include notes he wrote on his evening at Camp Downey. So, I faced not just the chance of finding where he stayed, but where he had written some of his thoughts. He wrote: “Two beings love each other. But they don’t speak the same language. One of them speaks both languages, but the second language very imperfectly. It suffices for them to love each other.”[6]

Well, Camus certainly was quickly smitten by Blake. Lottman notes that Camus attempted to get his travel companion to take them back to New York City rather than continue to Montreal. Biographer Oliver Todd wrote that Camus shared with his good friend Pierre Rubé “that he felt very much in love” with Blake.[7]

Despite what anyone might think of Camus’ choices, he wasn’t a heartless, casual philanderer. His published writings hint of his urges, even, surprisingly, in The Myth of Sisyphus. “Why should it be essential to love rarely in order to love much.”[8] And, “What Don Juan realizes in action is an ethic of quantity, whereas the saint, on the contrary, tends toward quality.”[9]

Camus was married to Francine, who was in France, and committed to Blake. He entrusted Blake with typing pages of The Plague and read her sections of this work-in-progress. He saw her almost daily, went to museums and plays with her, and spent as many hours with her as possible. She was his New York confidant of creativity, illness, and melancholy.

What remains of the former Camp Downey — photo by the author, 1997.

Clayburg is a hamlet smaller today than it was 100 years ago. I’d been through it numerous times, without realizing it. It sits on State Route 3, halfway between Saranac Lake and Plattsburg, New York. Today, most of the hamlet’s pre–World War II buildings are gone, with nothing on Route 3 resembling an inn. It’s a town that was probably into an economic decline before Camus’ visit, in 1946.

After driving through Clayburg in both directions on Route 3, without finding a hint of Camp Downey, I took a crossroad that angled northwest from Route 3. A few hundred yards up that road I spotted a mailbox on the left, across from an abandoned house. I slowed to see if there was a name on the mailbox and, obscured by a shrub, I was able to make out the name Downey.

The abandoned house was a smallish, two-story wood-framed house, far below the scale of what could have been an inn. But between it and the road there were remnants of a paved, circular driveway. An odd detail about the house is that its front porch features a foundation, and four asymmetrically placed columns, crafted from rounded river stones of grandeur and style exceeding that of the house behind it. Beyond a wide side lawn to the west is a small, silted pond. Walking up the front steps of the house I found a for-sale sign lying on the porch, with a phone number on it. Calling that number I spoke briefly with someone who told me that, yes, that house had for decades been known as Camp Downey.

Camp Downey, postcard published by Eastern Illustrating Co., Belfast, ME. From the author’s personal collection.

I was thrilled to find exactly where Camus had stayed in the Adirondacks. It still existed. I had found where Camus had spent a night ostensively in my own backyard.

While Camus was at Camp Downey, he added the following creative inspiration to his journal: “Small inn in the heart of the Adirondacks a thousand miles from everything. Entering my room, this strange feeling: during a business trip a man arrives, without any preconceived idea, at a remote inn in the wilderness. And there, the silence of nature, the simplicity of the room, the remoteness of everything, make him decide to stay there permanently, to cut all ties with what had been his life and to send no news of himself to anyone.”[10]

Camus also wrote in a letter to Blake: “I think you’d like this place, lost in the Adirondacks, where we have landed after two days of wandering in the mountains of this region. It’s an isolated old house which is usually visited by hunters and fishermen, but which is deserted right now. I am in the living room in front of a big fireplace, under a beamed ceiling. There was a storm a moment ago and now the night silence is full of the cries of toads, birds, and crickets. My dear, I was so unhappy to have left you and so displeased with myself…. The only desire that is worth anything is the one to keep you near me.”[11]

A day after finding the house I located John Downey, a great grandson of the builder of the inn. He shared that the property been passed down through four generations, with original construction beginning in 1850, expanding into an inn in 1912. In 1947, a year after Camus was there, John’s grandfather died and his father took over ownership, closing the inn around 1949 because it no longer supported itself. He added that, in 1962, the main part of the inn was torn down, leaving just the small section that stands today. In the missing part is where the fireplace stood that Camus mentioned in his letter to Blake. In the time since I first visited what remains of Camp Downey in 1997, it was sold and remodeled with additions. Downey confided that the camp’s registers had been discarded.

My heart sank from those last bits of John Downey’s news, but not too much. The porch, the pond, even the croaking toads, are all still there. In fact, enough is still there so that the there is still there, and I now know where that there is. Also remaining is the ambience of the Adirondacks that Camus felt around him and… wait, he was there in late May?! As anyone familiar with the Adirondacks knows, the black flies are unbearable in May. It’s not surprising the inn was deserted.

My having found Camp Downey, having found where Camus had lived for a few moments, putting his thoughts onto paper in my familiar Adirondacks, anchored him to me as real person. I had, through proxy of place, stood next to Camus. Where I’ve been atop Whiteface Mountain, where I have toppled a canoe into Fourth Lake, stood above John Brown’s grave, camped at Seventh Lake, spent many summer days and nights, Camus is now connected to those places and my lived memories. I have been witness to Camus, if only through the coincidence of place. Camp Downey is a bridge between us.

The notes and letters that Camus authored in America, and the accounts of those who met him, reveal his insatiable longing for love and his anxiety of separation, both of which permeate his literature. About New York City he wrote: “In the middle of the night sometimes, above the skyscrapers, across hundreds of high walls, the cry of a tugboat would meet my insomnia, reminding me that this desert of iron and cement was also an island. I would think of the sea then, and imagine myself on the shore of my own land.”[12]

About Camus and love, Simone de Beauvoir has shared that one evening Camus told her, “You have to choose: it either lasts or it ignites; the drama is that it can’t last and ignite at the same time.”[13] We are left to wonder, though, whether Camus considered himself Mozart’s Don Giovani or Lord Byron’s Don Juan—seducer or victim.

Pondering Camus’s writings from his night at Downey, I find hints of inspiration for his short story “The Adulterous Woman,” a story of a married woman unfulfilled because she cannot share her deepest feelings with her husband. On a journey, they stop at an inn. While her husband sleeps, she sneaks out to be by herself to consecrate her loneliness with the silence of the night. Her adultery isn’t of the flesh but of her essence, committing adultery with a secret affair with her nostalgia for a life she desires but is unable to live. It’s adultery because until then she had been living in denial, but from that night forward she was living in deceit.

Needy for love, tragically depressed, a melancholic romantic, impatiently nostalgic, Camus wrote: “I’ve always been calm at the sea, and for a moment this infinite solitude is good for me, although today I have the impression that this sea is made of all the tears in the world.”[14] Alone in early spring in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, Camus suffered an aching heart. But investing too much into so few of his words can be an unreasonable speculation.

Lottman reports in his biography of Camus that Camus and Liebling continued their friendship until Camus’s death, with Liebling often visiting him in France. Within a few years of Camus’s death, Liebling’s health declined, and he became clinically depressed. In 1963, Liebling and his wife, Jean Stafford, visited Algeria. Lottman recounts that Stafford later shared that Liebling had taken them there in search of his deceased friend.[15] One might ask, why Algeria if Camus’s grave is in France, Camus’s books were in Liebling’s library, and Liebling’s personal memories of Camus were in the streets, bars, and Bowery of New York City? It’s because the antecedents of Camus’ creations are primarily in Algeria, so that’s where Liebling believed he might find the empathy and reconnection he desperately sought. I picture an ailing, melancholic Liebling, with his wife in tow, looking for his absent friend on the southern shores of the Mediterranean. It is a heartbreaking nostalgia Camus would fully endorse.

If one day I find myself in Algeria, wandering the streets of Oran, the ruins of Tipasa or Djemila, I’ll respect the enduring friendship of Camus and Liebling and honor our thirsts for empathies. There, I will look for Camus, and I will look for Liebling looking for Camus, and I will look for Camus looking for Camus.

Notes

[1] Albert Camus, “On Jean-Paul Sartre’s La Nausée,” in Lyrical and Critical Essays (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Vintage Books Edition, 1970) 199.

[2] A. J. Liebling, “Talk of the Town,” in The New Yorker, April 20, 1946 (The F. R. Publishing Corporation 1946) 22.

[3] Camus, “The Rains of New York,” in Lyrical and Critical Essays, 186.

[4] Herbert R. Lottman, Albert Camus a Biography (Gingko Press Inc. 1997) 411.

[5] Camus, “The Rains of New York,” in Lyrical and Critical Essays, 183.

[6] Albert Camus, American Journals (Marlowe & Company, 1987) 48.

[7] Oliver Todd, Albert Camus A Life (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1997) 222.

[8] Albert Camus, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” The Myth of Sisyphus & Other Essays (Vintage Books A Division of Random House, 1955) 52.

[9] Albert Camus, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” The Myth of Sisyphus & Other Essays 54.

[10] Albert Camus, American Journals 48.

[11] Oliver Todd, Albert Camus A Life 224-225.

[12] Camus, “The Rains of New York,” in Lyrical and Critical Essays,185.

[13] Herbert R. Lottman, Albert Camus a Biography 390.

[14] Albert Camus, American Journals 59.

[15] Herbert R. Lottman, Albert Camus a Biography 408.